Families remaining behind: I mpacts of migration on families and children’s education

Kristina Mejo, IOM Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

International migration continues to grow at a significant pace. In 2013, there are an estimated 232 million international migrants living abroad. This is a consistent rise since 1990, when 154 million international migrants were living abroad. The number of international migrants is expected to reach up to 405 million by 2050 (Global Migration Group, 2013).

Coupled with the increase in international migration, remittances too have seen a significant growth. Developing countries received USD 401 billion in 2012 from remittances, almost double from 2006 (USD 221 billion) (Ardittis & Laczko, 2013).

Coupled with the increase in international migration, remittances too have seen a significant growth. Developing countries received USD 401 billion in 2012 from remittances, almost double from 2006 (USD 221 billion) (Ardittis & Laczko, 2013).According to a 2012 IOM Sri Lanka study, international labour migration has improved access to financial resources to families remaining behind. This said, it was found that the “effects are not-universally realized.” (Sri Lanka Migration Health Study: Study on Families Left Behind, IOM, 2012).

Feminization of migrationThe impact of migration on families in countries of origin can be reflected at various levels, and gendered dimensions are revealed in both migration and remittance trends.

Today, the feminization of migration is a notable characteristic of the globalized workforce with women making up 48% of all international migrants. When women enter into the labour force, remunerated for their work and able to send remittances home, they consequently are enabled with “greater influence and power in their respective families and communities of origin.” (Lopez-Ekra et al., 2011).

This is an important element to consider when analyzing the power dynamics of migration, particularly surrounding empowerment of women to exercise choice and influence.In addition, globally, women account for 50% of all remittances beneficiaries (Ibid). Studies note that women tend to spend remittances more on “education, health and nutrition” while men more “business and property.” (Ibid). A World Bank Study in Ghana found that if the wife is the main recipient of remittances (from her husband), there is a greater allocation on education, while if the husband is the main recipient, the allocation to education actually decreases (Ibid).

Positive impacts on children’s education

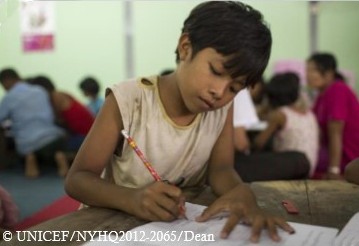

For children who remain in the country of origin, the predominant concerns are around “their social, educational, behavioral and psychological development.” (Sri Lanka Migration Health Study:Study on Families Left Behind, IOM, 2012).

Apart from monetary gains associated with migration, exposure to new cultures and values by one or more parent can positively impact children’s education. This, coupled with the greater awareness of children’s right to education, can ultimately enhance access to education for those children remaining behind. In fact, being able to support children’s education “is often a decisive factor” influencing children’s parents to migrate (Lopez - Ekra et al., 2011).

According to the Bangladesh Household Remittance Survey 2009, which interviewed 10,673 households, the primary use of remittances (over 80% of respondents) was geared towards meeting family expenses (divided between disposable goods and services and durable goods and services) (IOM).

The survey indicated that remittances led to improvements in the consumption of food among the majority of households with at least one member abroad. Remittances also had a “positive impact on the level of educational opportunities available in the migrant households. Approximately 82% of the surveyed households mentioned using remittances to buy books, paper, and other learning materials and 66% mentioned using it to pay tuition fees/exam fees/transportation costs for their children.”

The survey indicated that remittances led to improvements in the consumption of food among the majority of households with at least one member abroad. Remittances also had a “positive impact on the level of educational opportunities available in the migrant households. Approximately 82% of the surveyed households mentioned using remittances to buy books, paper, and other learning materials and 66% mentioned using it to pay tuition fees/exam fees/transportation costs for their children.”

Moreover, it was found in the Philippines that children of migrant workers who remained behind were enrolled in private schools, and actually fared better in school and had better attendance rates than those who came from non-migrant households (Lopez-Ekra et al., 2011).

Migration can be a barrier to girls’ education

Despite these positive influences, it is important to note that the departure of one or more family members through migration, can also lead to adverse effects, given the absence in the family to support the household. For example, in the case of rural households in China young girls are more likely than their brothers to be taken out of school in order to help their mothers with chores and farm work or to care for younger siblings (IOM, 2009).

Migration of one or more members of the family indisputably affects the family left behind. This can be seen through various components: economic, social, gender roles, and the division of labour at home. These elements also impact the overall wellbeing and education of children.

Education provides lifelong opportunities for children. While international migration can have potentially positive or negative impacts, the growth of migration and remittances alike can be harnessed for the advancement of international migrants and their families, and notably the education of those children remaining behind.

Edited by Jessica Aumann