In Photos: Women on the front lines of COVID-19 in India

Date: 18 August 2021

With less than one doctor for every thousand people, and a medical system stretched to its seams, women have shouldered an enormous burden of care since the pandemic started in India. Women make up 47 per cent of all health workers and more than 80 per cent of nurses and midwives, working at the front lines of COVID-19, risking exposure to the virus.

Women also make up the majority of workers in service and social work sectors. In India, women workers and volunteers from non-profit organizations like the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) distributed rations, essential commodities and provided information about COVID-19 prevention to women and girls from the poorest and most marginalized communities. SEWA is a long-standing partner of UN Women for economic empowerment programmes in India.

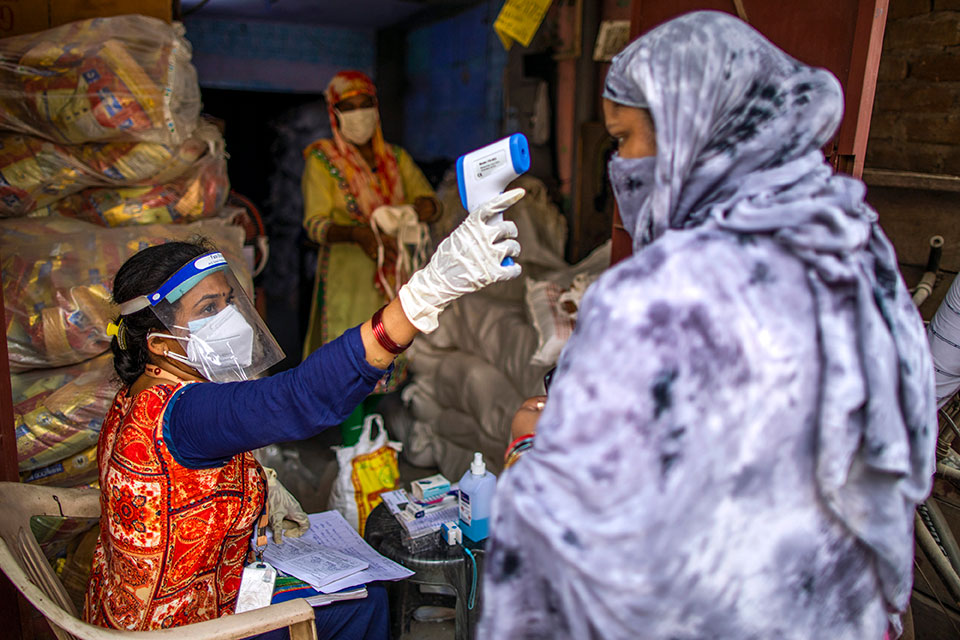

Rehana Chaton works as a Anganwadi worker at the Saheli Samanvay Kendra (SSK) in Batla House, New Delhi. These community centres set up by the Indian Government across the country act as local incubation centres to promote women’s self-help groups, provide skills training and public health information. The SSKs operate within Anganwadi centres that are part of the Indian public health care system, providing basic health care services and education for children in rural and marginalized areas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the centres have remained open, providing free meals, immunization and health check-ups for children, pregnant and lactating mothers, and helping women access government assistance programmes.

Even during the COVID-19 lockdowns, Rehana worked at the SSK centre in the Batla House area of New Delhi, distributing rations, protective masks and providing immunization and basic health services. “There were problems with travelling during the lockdown as we live far away and had to walk the whole way. We went door to door to distribute rations and masks twice a month. Many people didn’t open their doors because they were scared they would contract COVID,” she shared.

The rations include staples, such as rice, legumes, oil, spices, milk, tea and sugar. “The rations last one week,” said Parveen, who met Rehana during one of her door-to-door visits. “We are a couple with four children. [My husband] is a daily wage labourer and I work as a domestic worker. After the COVID lockdowns, work hasn’t resumed.”

The SSK and Anganwadi centres also provide livelihood skills to women. Non-profit organizations like SEWA help women access small loans, learn tailoring and sewing, as well as computer skills and beautician training to improve their income. Other organizations, like CEQUIN and Azad Foundation also active in SSK centres and Anganwadi centres, are working with UN Women and the Ministry of Women and Child Development in India to develop action plans to help women and girls from the most marginalized communities and those at risk of gender-based violence.

Women’s job loss and safe transportation during the pandemic continue to be pressing concerns in India. Organizations like the Azad Foundation supports Sakha Cabs – taxi services by women, which continues to employ women in five major Indian cities – Delhi, Jaipur, Kolkata, Indore and Chennai. During the lockdowns, they remained open as essential services. At a time when COVID patients and their families struggled to find local taxi service, Sakha Cab drivers transported them safely, equipped with masks, gloves, hand sanitizers and face shields.

Lalita, 27, is a driver with Sakha Cabs in New Delhi. She lives with her parents and siblings and is the only working woman in her family. It’s important for her to work, but driving cabs comes with safety concerns, especially when travelling at night. “Driving men at night sometimes feels unsafe, especially when they ask for your phone number… We get pepper sprays to carry and have an emergency button in the car,” she says.

At home, even prior to the pandemic, Indian women spent 9.8 times more time than men on unpaid domestic and care work. The pandemic lockdowns increased women’s care burden exponentially, around the world, and in India.

Alpana Devi, 25, supports her family through tailoring and embroidery work with SEWA’s Ruhaab programme centre in New Ashok Nagar, New Delhi. During the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, her husband lost his job, but after a two-month pause, she was able to start her work at the SEWA community centre.

This year, when the second wave of COVID-19 hit India and her husband lost his job again, they went back to their village. Alpana Devi returned to the city in June 2021 with her 6-year-old son, Monty, and went back to work, stitching masks and other materials at the SEWA centre that she could sell to earn an income. Because of COVID-19 lockdowns, Monty studies at home. Like millions of working mothers, Alpana Devi juggles childcare while trying to maintain her income.

How you can help

- Donate to UN Women and women’s organizations in India to build back from COVID-19.

- Learn more about the crisis in India.

- Read the Frequently Asked Questions about COVID-19 and women in India.