Snapshot of Women’s Leadership in Asia and the Pacific

Gender-equality and women’s empowerment is a pre-condition for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals[1]. Beyond a moral and ethical imperative, women’s effective participation and leadership has the potential to improve productivity, enhance ecosystem conservation, and to create more sustainable systems[2]. In Asia and the Pacific, women’s role as leaders and agents of change is being increasingly recognized. In recent years, governments, political bodies, businesses, and corporations have moved towards gender parity, although this progress remains slow[3].

Representation in Politics

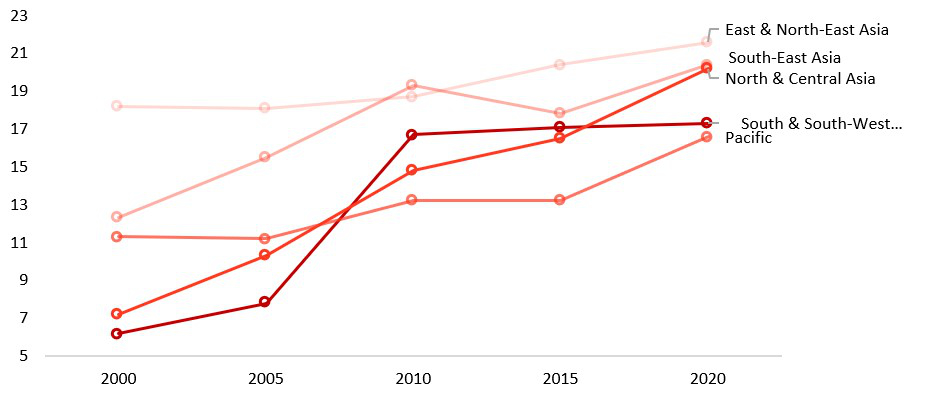

In Asia-Pacific, women’s representation in parliament has increased over the past two decades (Figure 1). While only 13 per cent of seats in national parliaments were held by women in 2000, this figure stood at 20 per cent in 2020[4]. This aggregate, however, still falls below the global average of 25 per cent, and representation is even lower in some subregions. South and South-West Asia and the Pacific lag the furthest behind, with only 17 per cent of seats held by women. Progress in women’s political participation has been made at an unequal rate, with some of the regions with lowest representation rates at the beginning of the millennium, such as North and Central Asia, seeing the largest increases (13 percentage points) in the past 20 years. While regions such as East and North East Asia are faring better (representation stands at 22 per cent) progress has been slight in the past 20 years, highlighting the need to actively continue promoting participation, including through parliamentary quotas.

Figure 1: Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments, by sub-regions in Asia and the Pacific, 2000-2020 (percentage)

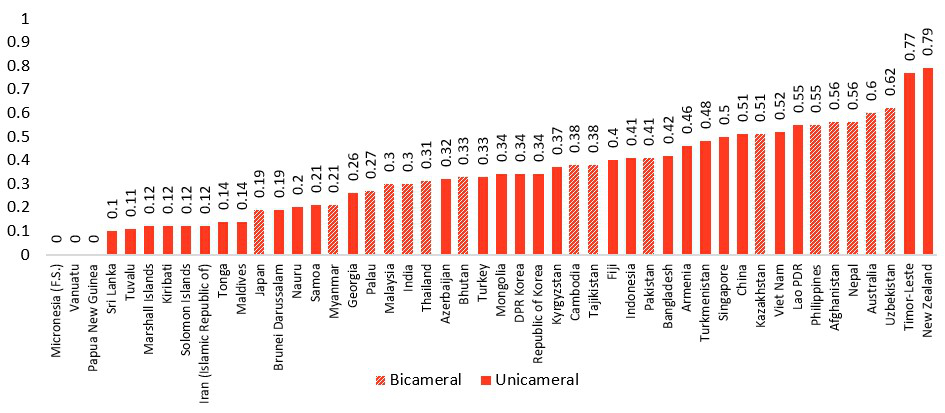

A fair share of women in public institutions can make women and girls in society feel closer to elected representatives who resemble them[5]. This can further increase their engagement in society[6]. In Asia-Pacific, the composition of national legislatures is far from representative relative to national demographics (Figure 2) – meaning that women and girls do not occupy roughly 50 per cent of positions (which is their approximate proportion of the overall population) in any of the countries. Furthermore, in a staggering 33 per cent of countries, women’s representation in national legislatures falls below 25 per cent of their relative share in society. Increasing the representation of women with different backgrounds, including rural women and women of minority ethnicities, is important to ensure decision-making takes into consideration the relative needs of the overall population.

Figure 2: Relative proportion of positions in national legislatures occupied by women compared to national distributions, by country and type of legislature (unicameral and bicameral), 2020

in parliament; 1=proportion of women in parliament equals that in the proportion of women among the national population; <1= proportion

of women in parliament is lower than that in the national population; >1=proportion of women in parliament is higher than that in the national

population

Ministerial positions and leadership in permanent committees

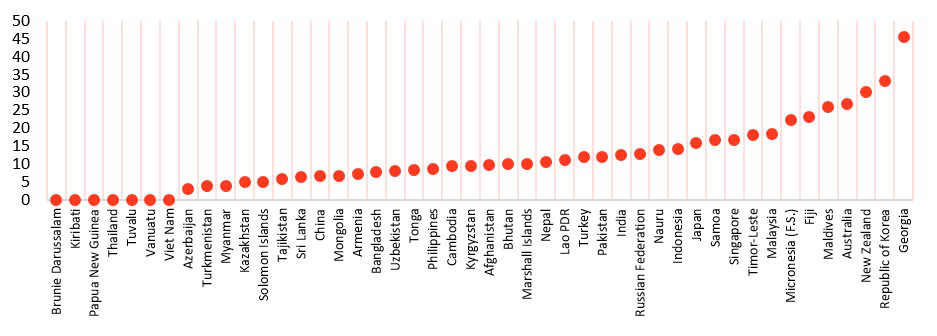

Ensuring women are represented among heads of ministries may create avenues towards gender-sensitive policy making. None of the countries in Asia-Pacific have reached parity in this area yet, with some countries observing a complete absence of women in ministerial positions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of women in ministerial positions, as of 1st January 2020 (percentage)

Across the region and globally, women’s ministerial roles are often restricted to portfolios such as family and social affairs. An alarmingly low number of women lead parliamentary affairs, population, defense, finance and human rights[7].

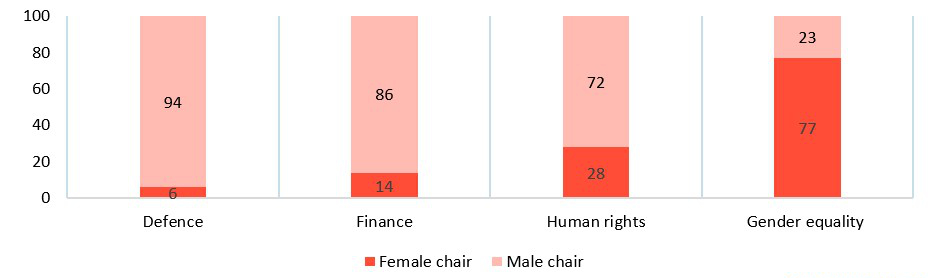

Women’s selective leadership is also apparent in their role as chairs of permanent committees. For instance, permanent committees on issues such as defense are rarely chaired by women. Among all countries with available data, Nepal is the only country with a female chair on a defense committee (lower chamber)[8]. Women are also underrepresented among chairs of permanent committees in charge of finance (females chair in 4 out of 29 countries) and human rights (females chair in 7 out of 25 countries). Women, in turn, are likelier to chair committees on Gender Equality, both in upper and lower chambers (females chair in 17 out of 22 countries).

Figure 4: Proportion of countries where at least one committee chair (upper or lower chamber) is held by a woman, by focus area of the committee (percentage)

Note: In Asia-Pacific, complete information on the sex of the chair of permanent committees is available for defense in 16 countries, finance

in 29 countries, human rights in 25 countries and Gender Equality in 22 countries.

Participation in local government

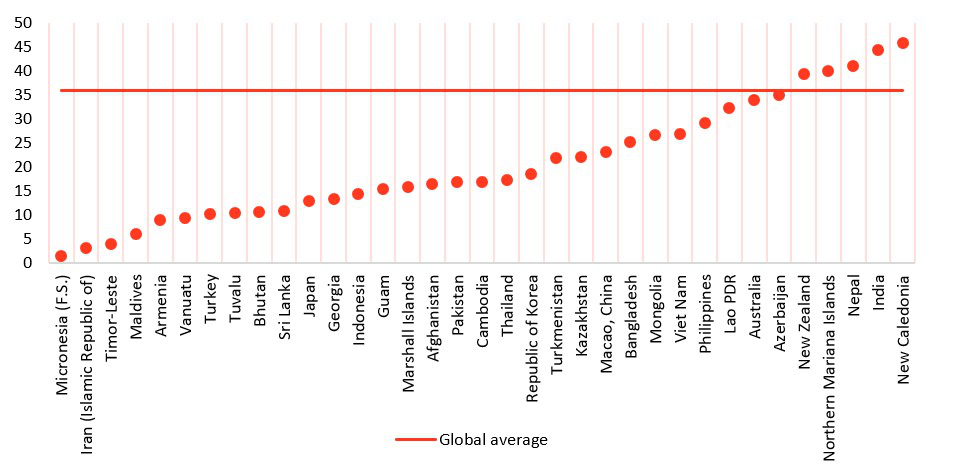

Women’s participation in deliberative bodies of local government is key in ensuring that policies respond to the needs of women and men in local communities, but most countries in Asia-Pacific fail to ensure parity in this regard (Figure 5). Elected representatives to local government are still overwhelmingly men: women’s representation in local government falls below the global average (36%) in 86%[9] of Asia-Pacific countries with available data.

Figure 5: Proportion of elected seats held by women in deliberative bodies of local government (percentage)

Environmental decision-making

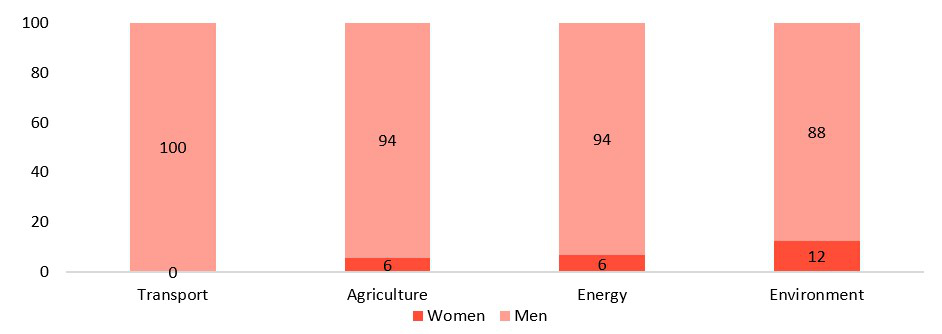

In Asia and the Pacific, women are also severely underrepresented as Ministers of environment and related sectors (Figure 6). Only 7 per cent of all environment-related ministries[10] (comprising agriculture, crude oil, climate change, energy, fisheries, irrigation, marine resources, mines, rural development, transportation, and others) have a female minister, compared to a global average of 12 per cent. In particular, women are largely absent from ministerial positions in ministries of agriculture (2 out of 36 countries (Bangladesh and Mongolia) have a female minister of agriculture[11] ) and energy (2 out of 31 countries (Bangladesh and Nepal) have a female minister of energy and related sectors[12]).

In countries with standalone ministries dedicated to environmental activities, women ministers are in place in only 4 out of 33 countries (Bhutan, Indonesia, Iran and Mongolia)[13]. In addition, no women hold ministerial positions in ministries of transport[14] in any of the countries with available data – a critical area for environmental conservation.

Figure 6: Proportion of countries with female ministers of environment and related sectors, by type of ministry (select ministries), 2015 (percentage)

is available for 30 countries, ministry of agriculture and related activities is available for 36 countries, ministry of energy and related activities

is available for 31 countries, and ministry of environment and related activities is available for 33 countries.

Because environmental conservation is highly related to agricultural activities, including forestry and fisheries, female decision-making in other forms of fora is also key. For instance, women’s leadership in forest committees and their managerial roles in fisheries, mining and logging industries can play a critical role in conservation. Data is scarce in this area, particularly regarding forestry and mining. However, available data for China, Japan and Thailand, indicates that only 13, 5 and 2 per cent of women respectively hold director positions in the seafood industry[15].

Influence at the peace table

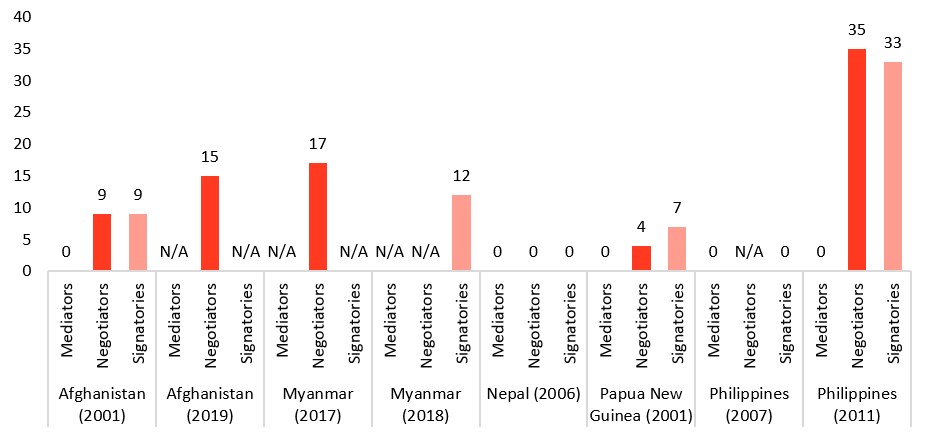

Experience shows that meaningful participation of women leaders across all stages of peace processes, both formal and informal, contributes to long lasting peace[16] . However, in Asia and the Pacific, women’s participation in peace negotiations as negotiators, mediators and signatories is notably rare. In countries with available data, women’s presence in major peace processes is often limited to negotiators and signatories. None of the countries with available data had a female mediator at the peace table (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Women's participation in peace processes, by type of role and country (percentage)

Connections between Presence and Influence. Available here. Data for the years 2011 and later are sourced from the Council on Foreign Relations.

Women managers in the private sector

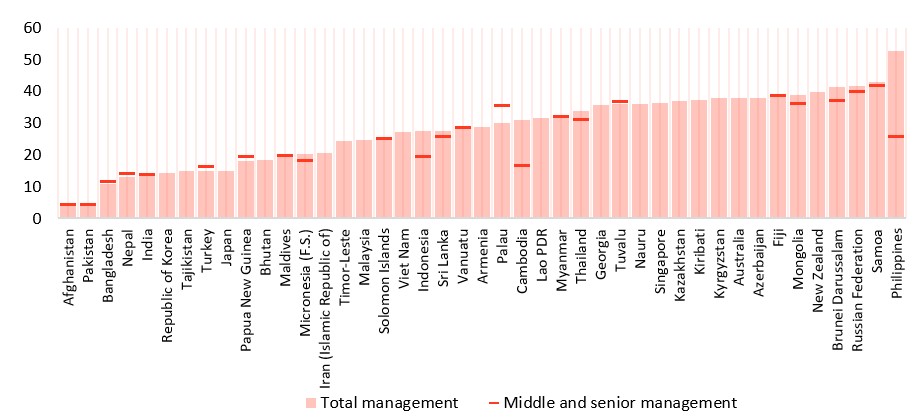

At 20 per cent, more women in Asia-Pacific hold managerial positions today than two decades ago, although progress in this regard has been slow. The largest gains have taken place in Eastern-Asia, where the rate of women managers increased from 18 percent to 28 per cent between 2000 and 2019 [17]. Parity, however, has not been achieved in the bulk of countries across the region (Figure 8). Worryingly, women’s representation in middle and senior management jobs is even lower: only 17 per cent of senior and middle management jobs in the region are occupied by women[18].

Figure 8: Proportion of women in managerial positions, by level of management (percentage)

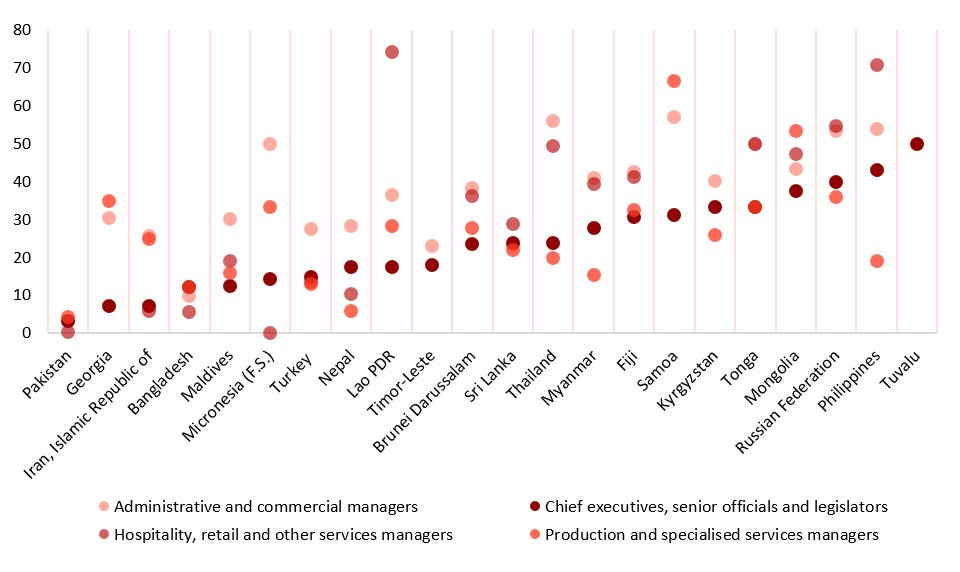

Evidence also shows that women’s employment in management roles is often concentrated in certain types of managerial functions (Figure 9). In Asia-Pacific, women account for 30 per cent of managers overseeing administrative and commercial activities, and 27 per cent of managers overseeing hospitality, retail and other services mangers. The share of women among chief executives, senior officials and legislators is 21 per cent, and that among production and specialized services managers only stands at 17 per cent [19].

Figure 9: Share of managerial positions occupied by women, by type of managerial function (percentage)

Women’s decision-making within the Household

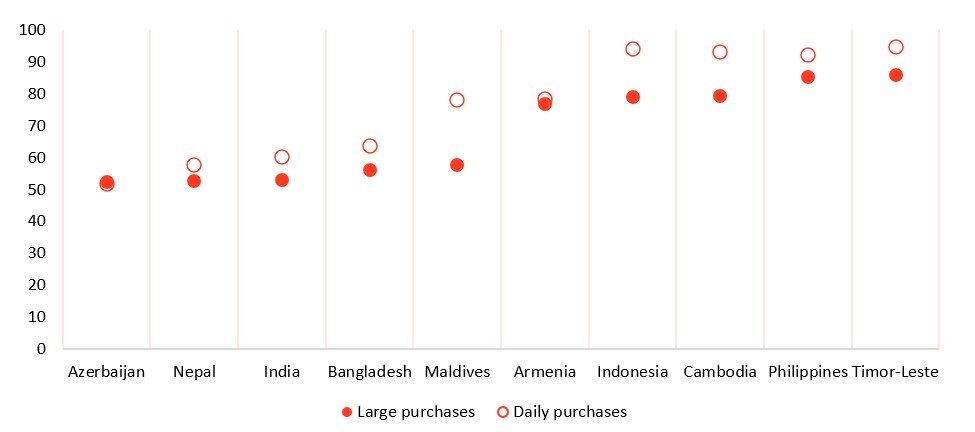

Unequal bargaining power and social norms also influence women’s participation in decision-making within their households. In Asia-Pacific, women are less likely to be able to weigh-in on issues around visiting family or seeing a doctor, but they typically make independent decisions about daily purchases for household needs. Women are also likelier than men to make decisions alone regarding large purchases, although these are more often made in consultation with their partners.

Figure 10: Proportion of women who have the final say in making household purchases, by type of purchase, 2005-2013 (percentage)

This factsheet was put together with the support of the Making Every Woman and Girl Count (Women Count) project in Asia and the Pacific.

See also:

-------------------------------------------

[1] UN Women https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2322UN%20Women%20Analysis%20on%20Women%20and%20SDGs.pdf

[2] UN Women (2014). https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2014/world-survey-on-the-role-of-women-in-development-2014-en.pdf?la=en&vs=3045

[3] UNESCAP (2019). https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/knowledge-products/Pathways_inf luence_promoting_role_wo men_transformative_leadership.pdf

[4] SDG Indicator Data. https://data.unescap.org/

[5] https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-16-07-01A.pdf

[6] Duflo, Esther (2012). Women’s empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 1051–1079.

[7] UN Women (2020). https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/women-in-politics-map-2020-en.pdf?la=en&vs=827

[8] Complete data on the sex of chair for defense committee is only available for 16 countries in the region. Out of these, 15 countries have a male chair. For each country with a bicameral parliamentary structure, the count considers “female chair” if at least 1 chamber (lower or upper) is chaired by a woman. For more details on these countries, please see the International Parliamentary Union database, available from: https://data.ipu.org/specialized-bodies?year=2021&month=1&structure=any&form_build_id=form-ESkdZdEsoNg-HWJwqcjW3mEbCi52ckb3nKne8PQF2PU&form_id=ipu__specialized_bodies_views_filter_form®ion=&sb_theme=4132&op=Show+items.

[9] Out of the 35 countries where this data is available, the proportion of elected seats held by women in deliberative bodies of local government falls below in global average (36%) in 30 countries. Data is available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database/

[10] According to IUCN’s 2015 classification, environment and related ministries include ministry of agriculture, irrigation, mines, transportation, energy, marine resources, fisheries, crude oil industry, ministry of climate change, ministry of rural development and others.

[11] For countries with available data, ministry of agriculture includes other complimentary profiles such as irrigation, forestry, and fisheries.

[12] For countries with available data, ministry of energy includes other complimentary profiles such as power, mines, mineral resources, and green technology.

[13] For countries with available data, ministry of environment includes other complimentary profiles such as forestry, human settlement, housing, green tourism, and others.

[14] For countries with available data, ministry of transport includes other complimentary profiles such as infrastructure, public works, and communications.

[15] FAO (2015). The role of women in the seafood industry. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-bc014e.pdf

[16] UNDESA https://www.un.org/en/desa/we-need-more-women-leaders-sustain-peace-and-development

[17] https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2020/secretary-general-sdg-report-2020--Statistical-Annex.pdf

[18] Regional aggregate is calculated based on country estimates, using population weights for working age population (15+) of women.

[19] Regional aggregate for women’s employment in managerial roles is calculated using women’s estimates from ILO database, using population weights for working age population of women (ages 15+).