Diana's Blog

We Need to Liberate ALL Women, Not Just the Elite

Dated: 2 May 2016

Years ago I took the bus with my mother near our home in Singapore. After we got off, my mother said, “It makes me so proud when I see female bus drivers or taxi drivers.” I also noticed the driver’s gender perfunctorily, the way one would notice the weather. Certainly not as strongly as my mother did.

When people discuss feminism in advanced countries, they always call for “empowerment.” But for me, this “empowerment” seems to be more about fighting for the rights of a narrow group of women instead of the rights of all women.

My understanding of feminism was given through my education, speaking volumes about how accessible feminism would seem to women who do not have the ability nor the need to speak within the framework of academia and theory. Kristin Aune and Catherine Redfern found during their research for Reclaiming The F-word that the factor that most affected whether people identified as feminists was higher education.

I grew up in a working class family, and for me, the conversation in the outside world around “women’s rights” felt like the domain of elite women. As American philosophy and politics professor Nancy Fraser said in a recent interview in The New York Times: “As I see it, the mainstream feminism of our time has adopted an approach that cannot achieve justice even for women, let alone for anyone else. The trouble is, this feminism is focused on encouraging educated middle-class women to ‘lean in’ and ‘crack the glass ceiling’ – in other words, to climb the corporate ladder. By definition, then, its beneficiaries can only be women of the professional-managerial class. And absent structural changes in capitalist society, those women can only benefit by leaning on others — by offloading their own care work and housework onto low-waged, precarious workers, typically racialized and/or immigrant women. So this is not, and cannot be, a feminism for all women!”

What would women like my mother care whether more rich women occupied powerful positions? These aren’t positions that are open to her. Women like her yearned for opportunities they could access, which included jobs like driving a bus. My mother worked as an assistant nurse before retiring to be a full-time housewife. There is a matter-of-factness in the way she speaks about the oppressions faced by women. She does not identify as a “feminist.” The term is too alien to her.

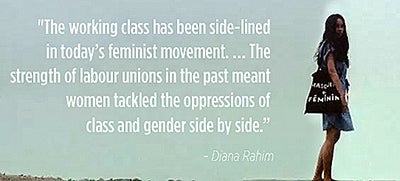

The working class has been side-lined in today’s feminist movement. One need only recall that International Women’s Day was once called International Working Women’s Day, and that the strength of labour unions in the past meant women tackled the oppressions of class and gender side by side. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development says that women do 75 per cent of all unpaid work globally, worth $10 trillion a year. Most of this work is domestic labour, not exactly a vocation sexy enough to be celebrated. Feminism and class has to be discussed together, like other issues that necessarily intersect, such as race and sexuality.

In Singapore, many working professionals hire female domestic workers to look after their homes and their children. These low-wage workers often face violence and discrimination because of their class as well as their gender. Yet their plight is rarely highlighted in conversations on women’s rights. Then there are the migrant sex workers who are ignored because of the stigma of their work, their gender and their status as migrants.

Even though feminist organizations work tirelessly to help and support women who go through duress, somehow the image portrayed by mainstream feminist discourse reflects an entirely different focus. Women of less-privileged backgrounds are often more likely to face gender-based violence, yet the very movement meant to support them – feminism – does not seem to give priority to their concerns. Focusing on “cracking the glass ceiling” is simply not inclusive enough.

Not all women are interested in being powerhouses. Some want to be bus drivers -- and that is as important a job to ensure equal access to as jobs in politics or business. As long as it is the woman’s choice, it is as valid and “empowered” a choice as any other.

Diana is from Singapore and volunteers with Gender Equality is Our Culture (GEC), a group that promotes gender equitable expressions of culture. She is primarily interested in the intersections of gender, religion and class. Visit: https://peachatoms.wordpress.com for more of her stories.