Passage of the Bangsamoro Organic Law promises new hope for women in Southern Philippines

Date:

Following decades of struggle for peace in southern Philippines, the Bangsamoro Organic Law was ratified in July 2018. The law creates a new political entity to replace the existing autonomous region, which is home to 13 ethno-linguistic groups in Mindanao. On 22 February 2019, the transitional authority took their oath of office, swearing in the new government’s Chief Minister, Cabinet and Parliament.

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) and what’s in it for women

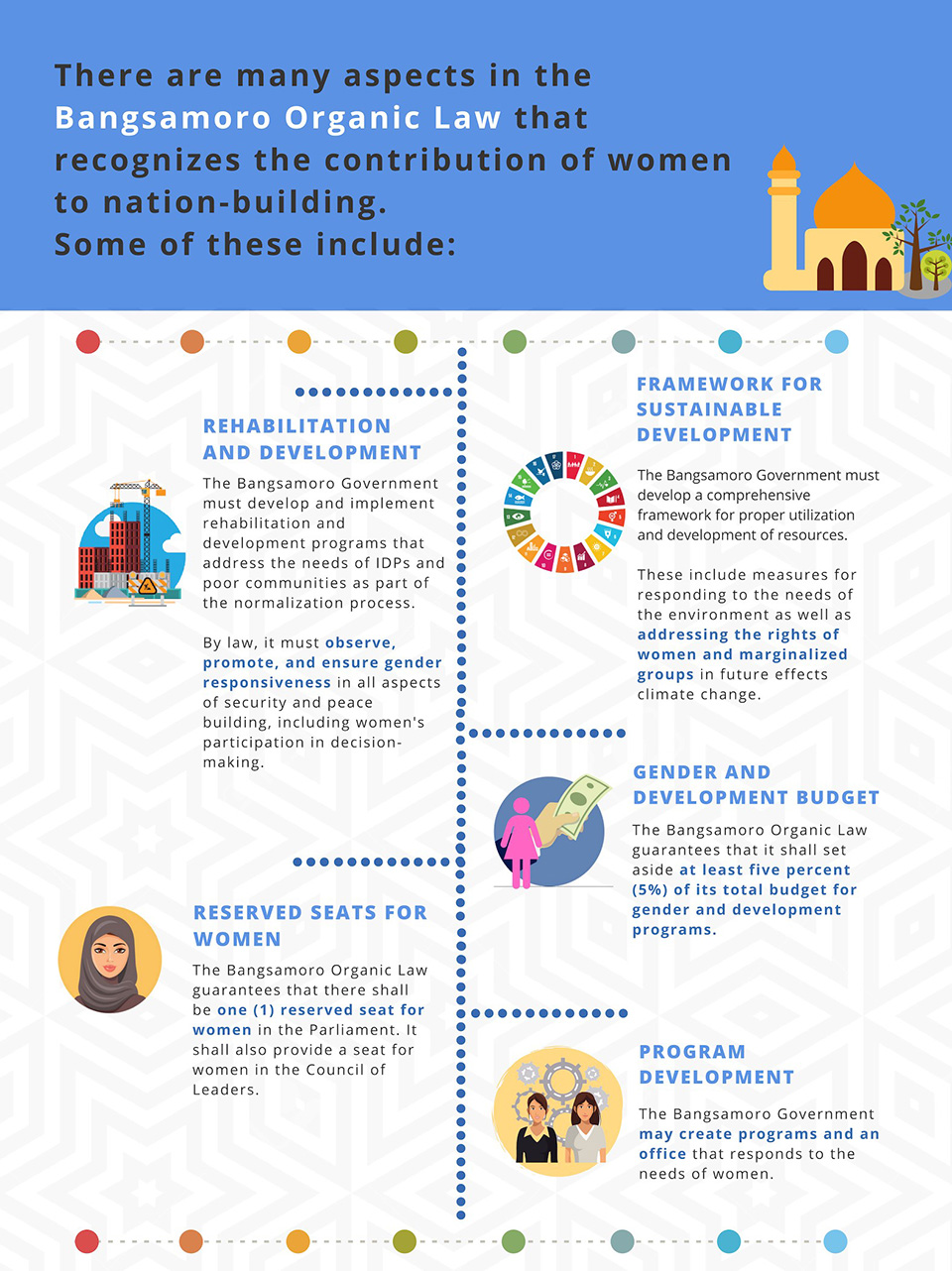

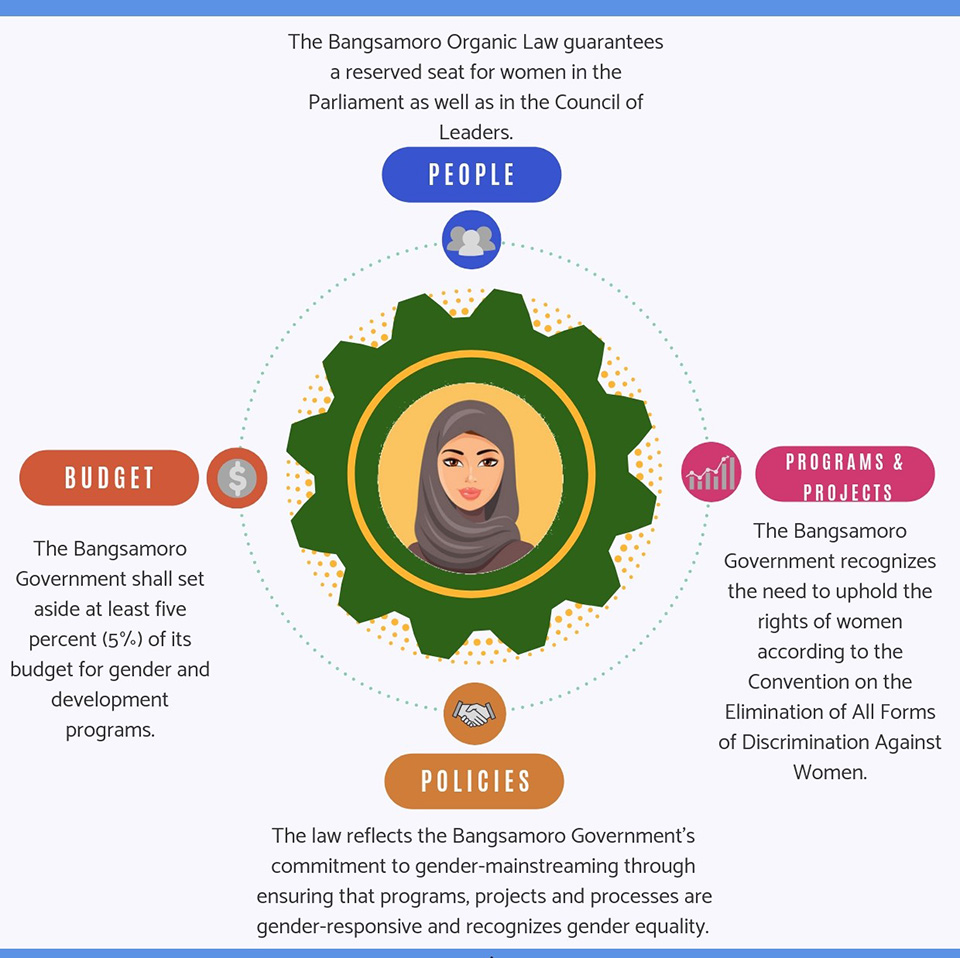

The newly-ratified Bangsamoro Organic Law contains several provisions that will benefit women and girls (see Figure 1). Women, youth and indigenous communities each have reserved seats in Parliament, and at least one woman must be appointed to the Cabinet. The law ensures an allocation of at least five per cent of the budget for programmes on gender and development. It calls for addressing the rights of women combatting climate change, and for women’s needs to be considered in rehabilitation and development programmes for internally-displaced people.

These provisions create a positive environment for women’s participation and gender-responsive governance. However, the advocacy and support from communities, NGOs and other actors – and the buy-in and support from government officials – will be vital to guarantee women’s rights and gender equality.

Women’s participation in the new government is critical to meeting women’s needs in laws and policies. These should be crafted in an inclusive process with women, youth and indigenous peoples. They must also consider the conflict, including threats of violent extremism, that has constantly challenged the region.

“We must take this time to involve women to lobby around issues that are important to us,” said Norsia Abdulgani of the Consortium of Bangsamoro Civil Society (CBCS), an umbrella organization closely monitoring the peace process, and one of UN Women’s partners.

Among the issues important to women in the new government, the first is a mechanism to promote, protect, and fulfil women’s human rights, such as a women’s commission or ministry. Guaranteeing women's access to justice, including transitional justice, is likewise a key concern. Lastly, it is crucial to ensure that government officials and personnel do not just understand women’s rights and needs, but also how to enable these to be met. This includes programmes that would address not only the practical needs of women, such housing and income, but also strategic needs, such as freedom from abuse and violence, land and property rights and non-discrimination.

UN Women’s support to the transition to the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

In 2015, UN Women began by training grass-roots women from the five provinces in leadership and advocacy. These women became advocates for equality and peace and developed as leaders in their communities. In 2017, these same women leaders gathered signatures from community members calling for the establishment of a transitional justice mechanism to respond to the historical injustices, human rights violations and marginalization of the Bangsamoro. The women then formed a Speakers’ Bureau to generate support for the passage of the Bangsamoro Organic Law in Moro diaspora communities.

UN Women has also supported women’s organizations to participate in monitoring of the peace agreement, to help prevent conflict in the Bangsamoro. Later this spring, the women’s organizations and mechanisms of the peace process will meet to discuss ensuring women’s participation in conflict prevention and protecting women and girls from violence.

For women to truly realize their rights and assume leadership roles in the new region, advocacy and training must be accompanied by increasing women’s empowerment – including their economic well-being. Eight communities in the BARMM are piloting a UN Women programme to empower women to prevent radicalization and recruitment of armed and violent extremist groups. Women participating in this project, entitled Empowered Women, Peaceful Communities, receive assistance to start and run small businesses and learn how to work together to promote peace. So far, 800 women and men have participated in the project.

“We need programmes not just for economic reasons but to make sure that we take care of our fellow women. We need to know each other's problems and find solutions collectively,” said one participant of the programme. Women are also advocating with their local governments provide support for these socioeconomic interventions to thrive.

In March, UN Women will hold a Women’s Summit bringing together women leaders and advocates trained through UN Women programmes. Leaders from the incoming Bangsamoro Transitional Authority will also attend to discuss commitments for gender-responsive governance and spaces for women’s participation in the new Bangsamoro.

“Through this meeting, we hope to facilitate an ongoing dialogue between women civil society leaders and networks and the incoming transitional government. The ultimate goal is to enable women’s meaningful participation going forward,” said Alison Davidian, UN Women Programme Specialist for Governance, Peace and Security.

The creation of the BARMM brings new hope to communities in the region. Whether those hopes are realized will depend on the willingness of the transitional government to fulfil the promises in the Bangsamoro Organic Law and to include women in every step of the process.