The gender technology gap has to end

Date:

Authors: Mohammad Naciri and Atsuko Okuda

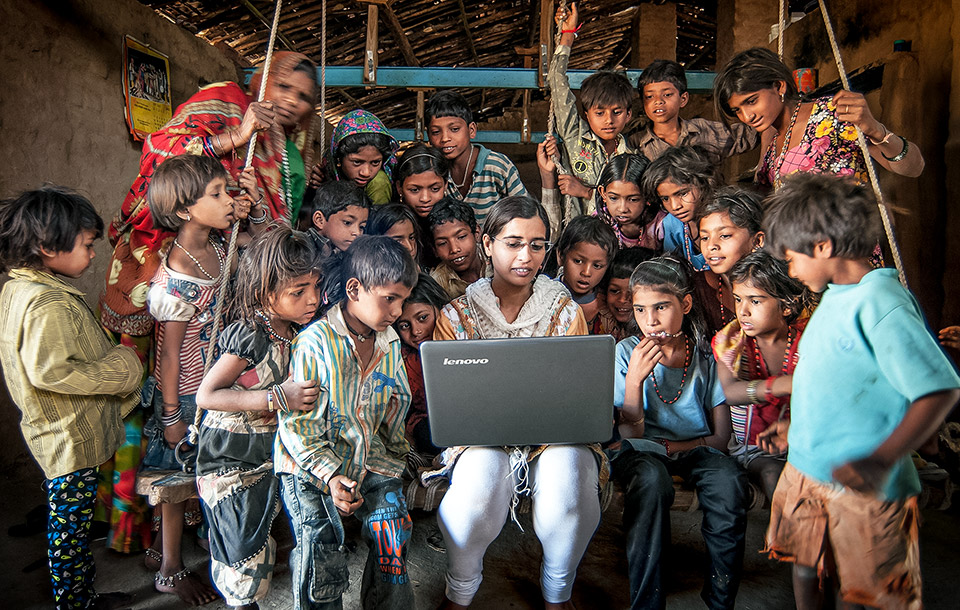

There needs to be a feminist approach to technology to solve the social impacts of the South Asian COVID-19 crisis

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has swept South Asia in recent months, existing inequalities have come to light. One aspect stands out: access to technology has never been so crucial to ensuring public health and safety.

Around the world, information and access to health care have largely moved online, and those left behind face grave disadvantages.

Limited or no access

According to Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA) estimates, over 390 million women in low- and middle-income countries do not have Internet access. South Asia has more than half of these women with only 65 per cent owning a mobile phone.

In India, only 14.9 per cent of women were reported to be using the Internet. This divide is deepened by earlier mandates to register online to get a vaccination appointment. Recent local data revealed that nearly 17 per cent more men than women have been vaccinated. While improving awareness of how to access vaccination and help are crucial to protecting women, the mindset around digital technology and device ownership must also change.

For example, when families share a digital device, it is more likely that the father or sons will be allowed to use it exclusively. In part, this is due to deeply held cultural beliefs: it is often believed that women’s access to technology will motivate them to challenge patriarchal societies. There is also a belief that women need to be protected, and that online content can be dangerous for women/expose them to risks. As a consequence, girls and women who ask for phones face suspicion and opposition.

These gaps prevent women and LGBTQIA+ people from accessing critical services. In India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, for example, fewer women than men received the necessary information to survive COVID-19. Vaccine registration usually requires a smartphone or laptop. Men and boys are thus more likely to get timely information and register than women and girls.

The concept of feminism goes beyond the rights of women. It is about a way of life. In simple terms, it means being inclusive, democratic, transparent, egalitarian, and offering opportunities for all. We can call it equality through innovation.

Feminist technology (sometimes called “femtech”) is an approach to technology and innovation that is inclusive, informed and responsive to the entire community with all its diversity.

Steps to an equitable future

At UN Women, we are encouraging companies to sign up and agree to principles that will lead to a more equitable future for all. As part of the Generation Equality Forum, the goal is to double the number of women and girls working in technology and innovation. By 2026, the aim is to reduce the gender digital divide and ensure universal digital literacy, while investing in feminist technology and innovation to support women’s leadership as innovators.

Through digital empowerment programmes and partnerships such as EQUALS and International Girls in ICT Day celebration across the region led by UN Women and the International Telecommunication Union, we hope that more girls will choose STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) as their academic focus, enter digital technology careers, and aspire to be the next leaders in digital technology.

What would the world look like if technology were truly inclusive and reflected our society’s needs? How would the world be different if feminist technology were embraced?

Hardly a neutral world

What we see today is that most technologies that are available to the layperson are created by men, for men, and do not necessarily meet everyone’s requirements. The supposedly neutral world of technology is full of examples of this: from video games to virtual assistants to the increasingly large dimensions of “handheld” smartphones, technology is not always made with everyone in mind.

Policy cannot solve this on its own, but the private sector can. Companies should not look at gender-equal technology solely from an altruistic perspective, but from a pragmatic one.

According to GSMA, closing the gender gap in mobile Internet usage in low- and middle-income countries would increase GDP by USD 700 billion over the next five years. Women and girls are the largest consumer groups left out of technology and could be major profit drivers.

In the App Store, there are about two million apps, most of which cater to young men. Why not design apps geared specifically towards mothers or apps for women to access telemedicine consultation? Or digital networks to connect women to informal job opportunities so they can still earn while balancing caring for their families? Other than apps, built-in features on mobile phones such as an emergency button connecting women to law enforcement if they face unwanted street harassment should also be considered.

Women and girls do not have the same access to these technologies as men and boys, nor are they available at the same price. That is not acceptable.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. In the 1950s, dishwashers and washing machines were promoted as a method of emancipating women. Household goods producers, for example, target most of their advertising at women because they often control the household budget. Digital technology could be approached similarly.

We now have the opportunity to shape our future in a way that is more equal, diverse, and sustainable in the world of technology in the aftermath of the medical and socioeconomic devastation in the past year.

Now is the time to act. The right thing to do is also the smart thing to do. Bringing an end to the gender technology gap will save lives and make livelihoods more secure. As a result, the next pandemic, once it arrives, may not be nearly as destructive. It can only lead to a better community and a better world for us all.