#ActForEqual: What did a series of conversations on gender equality in Sri Lanka reveal?

Date:

Author: Esther Hoole

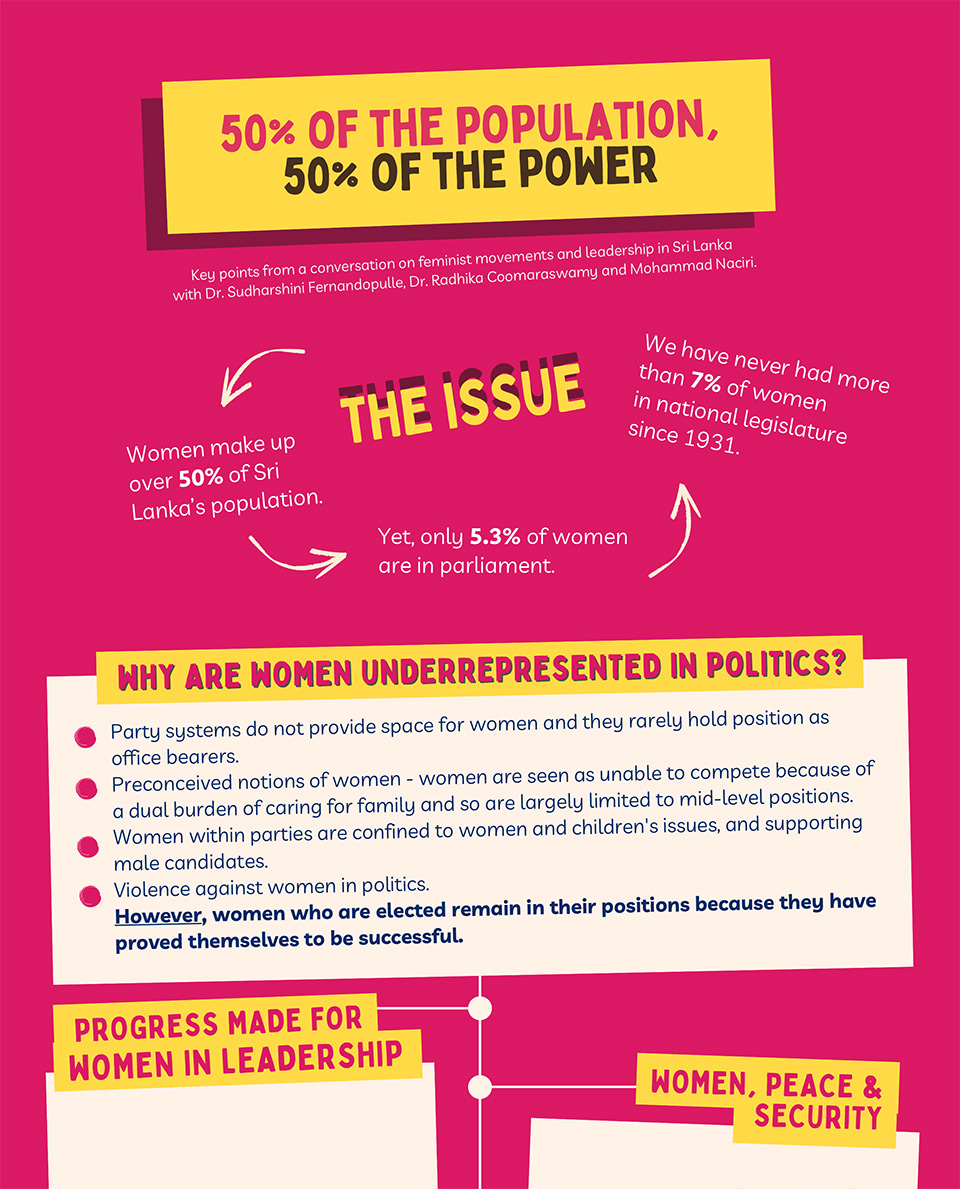

Sri Lanka’s national legislative body has never had more than 7 per cent of women legislators. 27 per cent more women undertake unpaid care work in comparison to men, while 73.7 per cent of Sri Lankan women were categorized as economically inactive. Almost 25 per cent of Sri Lankan women have suffered sexual or physical violence. Women are severely and disproportionately affected by climate change. They are increasingly objectified and attacked across traditional and new media. Nearly a third of Sri Lankan women are unable to afford sanitary pads due to 'luxury' tax, which has been worsened by the ongoing pandemic.

These statistics set the tone for a series of conversations jointly hosted by UN Women and the French Embassy in Sri Lanka, in the broader context of COVID-19 and the parallel worsening of gender equality. In the course of the six discussions – each based on the thematic focus areas of the Generation Equality Forum – experts and activists repeatedly highlighted three underlying problems in relation to gender equality and women’s rights in Sri Lanka.

1

Social stigma and gender norms

Socially reinforced gender norms in Sri Lanka relegate women to the position of passive dependents – at best, glorified as mothers and wives. At worst, objects to be used and dismissed. This was apparent across each of the themes discussed. Perceived to be poor leaders, women are systematically exempt from places of power. Perceived as natural caregivers, women bear a disproportional burden of unpaid care work in the home. Unable to commit to regular hours because of this disproportionate burden, women who do enter the work force are restricted to informal work sectors with little protection and benefits. The power imbalance caused by all of these – within the home as well as in public spaces – leave women exposed to violence and abuse.

2

Exemption of women from leadership

Flowing from the social norms that preclude women from leadership and decision-making, women are largely exempt from political fora, boardrooms, and leadership in media houses and scientific communities. Speakers across the discussions who are in positions of power also shared that once women have become leaders, their expertise continues to be undermined, their views dismissed, and their roles relegated to stereotypical “women’s issues”.

3

Inadequate social protection and empowerment of women

Tied to the lack of women’s representation in power, each discussion referred back to legal and policy frameworks which are either blatantly patriarchal in nature or fail to account for the specific challenges faced by women. In relation to the former, there is the categorization of women’s sanitary products as a “luxury”, the objectification and stigmatization of women in media, and laws which restrict women’s right to consent to marriage and sex. Other instances, such as agricultural and climate related policies which disregard women’s lack of access to and ownership of resources, a justice system which is often insensitive to and inadequate for survivors of gender-based violence, and the exclusion of women performing unpaid care work, flag that women’s nuanced experiences are not considered in forming and implementing polices.

Addressing these issues requires tailored solutions. Three broad points remain constant:

- Deep social advocacy and reform to combat historic and systematic gender-based prejudices and norms.

- More women in leadership from different communities to lead to inclusive, meaningful and intersectional decision-making to better represent viewpoints from all genders from all communities.

- Policies and institutional frameworks which ensure equal opportunities and rights for all genders to live in freedom and reach their fullest potential.

In Sri Lanka, there are signs of hope and change. A quota for women’s representation in local government now requires that 25 per cent of elected officials are women. More women are now reflected in these fora, and are countering existing assumptions on women in leadership. Women in parliament are advocating for similar affirmative action at national and provincial government levels. Employers in the private sector are taking active steps to cater to the needs of their female employees – providing for more flexible hours and working options, while also providing support in cases of violence.

While Sri Lanka has always had a strong women’s movement, it is growing louder and wider, with more women reflecting feminist leadership in science, business and media. As younger activists build broad and intersectional networks, men are also joining with women and members of the LGBTQ+ community to demand equality and empowerment for all.