Myanmar’s survivors of violence: Getting justice in the courts, not settlements in the community

Date:

Author: ActionAid Myanmar

Meiktila, Myanmar — She was a perfect target for human traffickers: an orphan, 20 years old, poor and with little chance to make any income, living with her siblings and grandmother in Yangon.

So the woman left when a broker promised a job in Meiktila, in the Mandalay Region, about 518 kilometres (322 miles) north of Yangon by road. But when she arrived, she was forced into prostitution. Both her main captor and his son beat her and raped her.

In the past, if Myanmar women like her managed to get the violence to stop, a little negotiation and exchange of money would have settled the matter. Now, new hope for true justice is being provided by local and international aid groups working in cooperation with the police and the courts.

While little hard data is available, conversations with women across the country suggest that violence both inside and outside the home is common in Myanmar. And the first and most basic struggle for women is that against traditional attitudes and customs.

Discriminatory attitudes were revealed in a survey done in February 2014 by ActionAid Myanmar, funded by the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women in the 4 selected regions of Myanmar namely Meiktila Township (in Mandalay Division), Pyapon Township (in Ayeyarwady Region), Kayah State, and Rakhine State. Many residents said: A woman should behave like a “good girl” and not wear clothes that attract men. A woman does not make decisions in the community, yet her family’s reputation in the community hinges on her behavior. When a woman is attacked, her dignity also is stripped away. And violence within the family is a private matter.

Thus, it is not surprising that there are few medical, psychological or legal support services for women and girls who survive violence. And weak laws and numerous bureaucratic hurdles make it difficult to get due process and access to justice.

In any case, traditionally such matters are settled by social custom rather than through legal institutions. Mediation in the community results in the assailant handing over a little money.

“The advantage for a woman is to get some money, but the perpetrator can do it again,” said a village leader in Meiktila. “Limited knowledge of the law in the village means that rape will mostly be solved through compensation.”

In other words, violent attacks are rarely reported to the police, while the traditional resolution perpetuates a culture of impunity in which assailants are merely reprimanded for “bad behavior”.

Civil society groups are trying to replace that with a culture of redress through law enforcement and legal institutions. As part of its Promoting Access to Justice: towards a violence free environment for women and girls project funded by the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women that began in December 2013, ActionAid Myanmar has trained 40 women across the country as paralegals who know how to respond to such cases and can report them to legal aid centres and the police.

Progress is being made. ActionAid Myanmar says that in the four States/Regions where it works, in 2014, paralegals had reported 22 such cases to Legal Clinic Myanmar, an NGO, while another 180 cases were called into a legal aid hotline. In 2015, paralegals reported 23 cases to the NGO, and another 730 cases were called into the hotline.

The 20-year-old from Yangon benefited from the new approach.

After six months of captivity, in September 2014, she made a desperate call to the hotline of the police’s human trafficking task force in Meiktila. She had seen a TV advertisement on the hotline, memorized the number, stole a phone from one of her captor’s clients, locked herself in a bathroom, and called the police. The police and township authorities rescued the woman and arrested all her assailants.

The woman was injured and scared so the police asked for help from the Myanmar Woman’s Affairs Federation, an NGO established by the government. The federation gave the woman a safe place to stay during the investigation and court proceedings. It also advised the police to contact ActionAid Myanmar to give the woman psychological and legal aid.

Two female staff members from ActionAid Myanmar met the woman at the police station, with no police officers present.

“At first she felt ashamed to talk about her injuries and the sexual violence, but we encouraged her to not feel shame or fear,” said Mya Thet Nwe, one of the ActionAid Myanmar staff members. “When we left, she seemed to be better already.”

ActionAid Myanmar in turn contacted Legal Clinic Myanmar, its local partner. Lawyers there reassured the woman that she had nothing to be ashamed about. They represented her at the legal proceedings and accompanied her each time she had to show up in court.

“If she had not received legal aid, I am not sure whether she would have even filed a case,” said Ms. Mya Thet Nwe. “The perpetrator had hired a very good lawyer, and tried to bribe the woman to avoid a court case. She was very afraid, but Legal Clinic Myanmar and the police encouraged her to stay strong. If the perpetrator were to go free, other girls would end up in the same situation.”

The woman’s main captor was given a 10-year prison sentence in December 2014.

The woman was offered vocational training and any other support she needed. But all she wanted was to return to her family in Yangon once her presence in court was no longer required.

She may have problems returning to society. In Myanmar, survivors of sexual violence are frequently stigmatized as having lost their dignity; among other things, they may face great difficulty finding men willing to marry them.

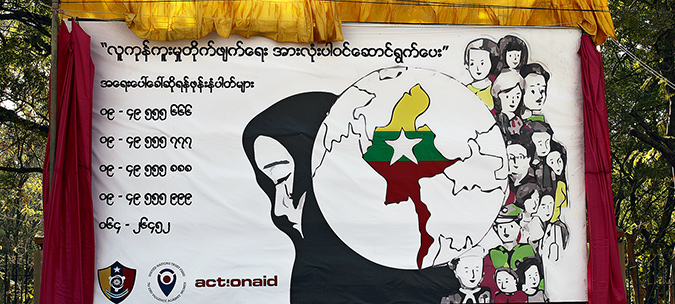

On 1 February 2016, the police’s human trafficking task force and ActionAid Myanmar put up a large billboard in front of Meiktila University displaying five emergency hotline numbers for survivors of violence and human trafficking. “Let’s fight human trafficking together,” the billboard says. It depicts a crying young woman, the national flag superimposed on an outline of Myanmar, and a gathering of people. The idea is to tell survivors: Even if you feel alone, the authorities, aid groups and members of the community are ready to support you. The billboard also reinforces the message that justice should be centered on the needs and the rights of the survivor.

The government’s National Strategic Plan for the Advancement of Women, for 2013-2022, outlines the need for new legislation against violence and for services that help women and girls feel more comfortable to report cases, including the hiring of more female police officers.

The ActionAid Myanmar survey in the four States/Regions also made clear, however, that raising awareness among men and boys is critical to efforts to end the violence. In the survey, a significantly higher percentage of men than women preferred simple scolding over harsher kinds of punishment for forced sex within marriage. Interestingly, however, a significantly higher percentage of men also preferred life imprisonment for rape over lighter kinds of punishment; they also preferred death sentences for human trafficking.

ActionAid Myanmar has trained 20 men to be “role models” who talk with other men in their communities about violence against women. In Mayut Chain village in Rakhine State, one such role model has persuaded at least four men in his village to stop beating their wives. They did not know that, “Beating your wife is not all right.”

About the Project

ActionAid Myanmar started “Promoting Access to Justice: towards a violence free environment for women and girls” with funding support from UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women in January 2013.

ActionAid Myanmar works with women and girls in 40 target communities in Myanmar to decrease in the incidence of violence and improvement in access to justice for women and girls experiencing violence through responsive, remedial and environment building interventions with stakeholders in communities, civil society, the media and the government.

For Further Information

Please contact: Nuntana Tangwinit

UN Trust Fund Focal Point for UN Women Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

E-mail: [ Click to reveal ]