Beijing+30 Youth Blog: Resisting oppression against the marginalized in the Asia-Pacific

Date:

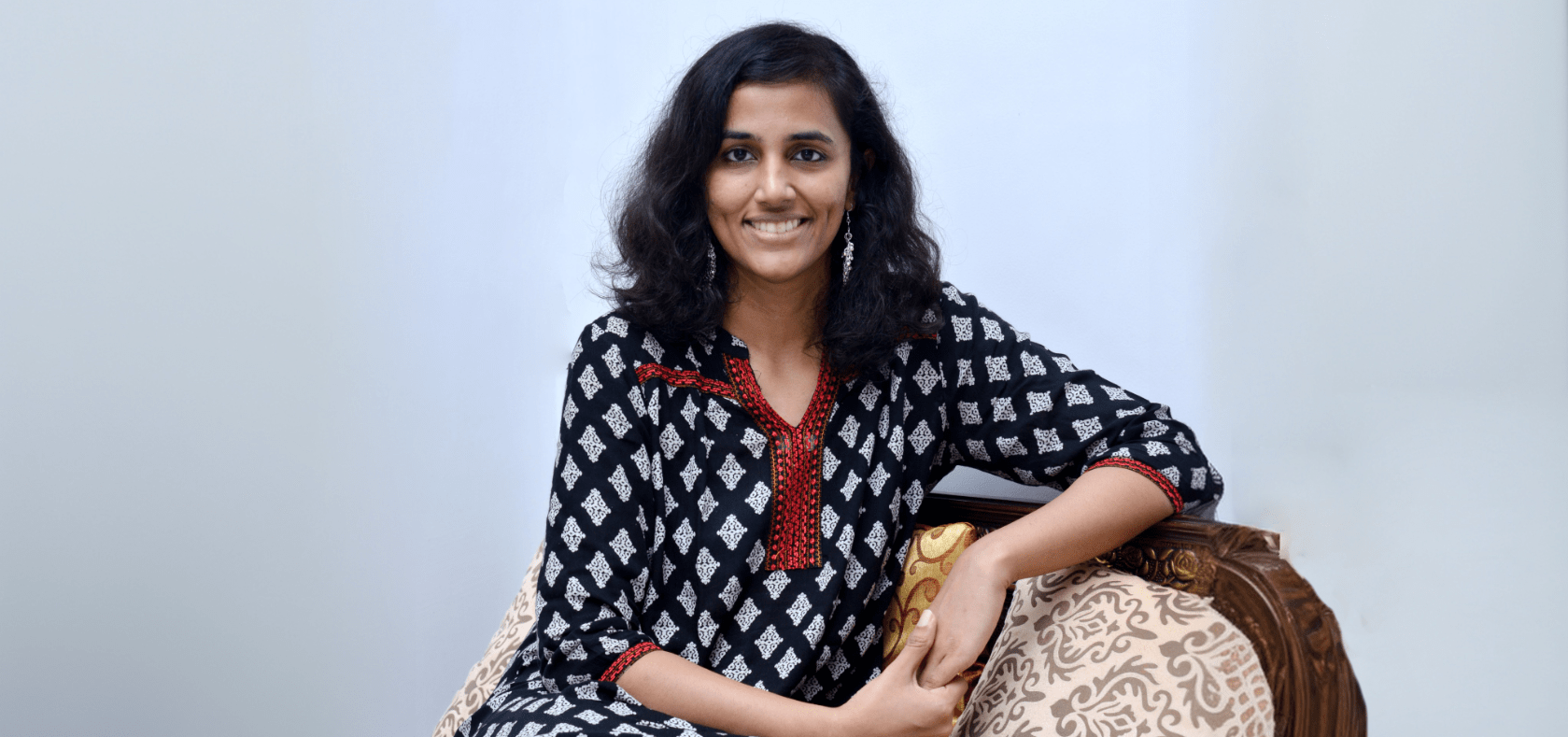

Author: Kirthi Jayakumar

When I first came across the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 2002, I had stars in my eyes. I was amazed as Hillary Clinton declared that “Women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.” It felt like a powerful affirmation of the full humanity of a woman.

With time, however, I would learn that the statement did not do much for women and girls who looked like me, or who came from parts of the world like mine. I would learn that this statement straitjackets “woman” into one category of woman, and excludes anyone who doesn’t fit in terms of race, caste, nationality, ability, sexuality, ethnicity, indigeneity, and much more. Over time, I came to understand that this statement overlooked a fundamental element in the feminist movement—a commitment to true equity through intersectionality.

Preceding the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, women of colour were silenced, sidelined or talked over. Françoise Vergès, in her book A Decolonial Feminism, wrote of how, at the World Conference on Women in Copenhagen in 1980, North African and Sub-Saharan feminists pushed back against the use of the terms “save customs” and “backward cultures”, used by Western feminists to denounce female-genital mutilation. Some of these issues endure in the run-up to the 30-year mark of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

With technological advancements, more and more feminists are able to mobilize and engage with each other in profoundly impactful ways. However, these spaces too often mirror existing power structures and systemic violence, perpetuating inequities that disproportionately impact those rendered vulnerable by their unique lived experiences and intersecting identities.

For instance, caste-based discrimination in South Asia makes education, employment, health care, and other resources inaccessible to women and girls from oppressed backgrounds while caste-privileged women are able to get ahead. Similarly, women and girls from minority religions and indigenous communities are more vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence across the Asia-Pacific. Queer indigenous women in the Pacific Islands simultaneously experience discrimination based on indigeneity, gender and sexual orientation, which renders them more vulnerable to climate change. And yet, the global discourse on climate change not only gives limited attention to gender dynamics but almost entirely overlooks the unique challenges and perspectives that indigeneity brings to these gendered experiences.

It’s time to recognize this reality and take decisive action: intersectionality within movements is essential. A key component for action is accountability, and accountability begins within the movement. Feminists who hold both positional and relational privilege must commit to accountability within the collective by redistributing their social capital, centering voices historically oppressed and marginalized, and moving away from practices of appropriation, occupation, and extraction. This requires a deep commitment to reflexivity and a sustained dedication to accountability within the feminist movement

Biography:

Kirthi Jayakumar, founded and runs The Gender Security Project in India, which researches the women, peace and security agenda and feminist foreign policy. She set up the CRSV Observatory to document conflict-related systemic and mass sexual violence. She is developing tools to facilitate feminist peace education and address conflict-related sexual violence. Jayakumar served as an advisor to the Women7 under the Italian (2024) Japanese (2023) and German (2022) presidencies of the G-7.

@kirthijayakumar |

@kirthijayakumar |  @kirthijayakumar

@kirthijayakumar